Colleagues:

Recent events have caused me to contemplate distinctions between simulation, on

one hand, and analysis, on the other.

AEH was asked to determine the root-causes of a thermal shift in the back focal

length of a lithographic lens. The optical design couldn’t predict

it.

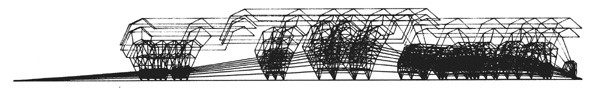

The optical, structural and thermal physics were modeled (we call it

“Unified”) in a single code, MSC/Nastran.

The deviations from the actual physics (including simplifications) were noted

and quantified. Check-out results were validated against CodeV to prove

their optical rigor. The analytical results agreed well with experimental

data. Their agreement was limited by the mesh in the finite element

model, which is typical in optomechanical problems, and it had been noted among

the deviations. The sources of the thermal shift became obvious in

reviewing the output data. These observables-in-the-data are called

“diagnostic vectors.”

AEH calls this approach “Unified

Analysis” because it keeps all the data together in a unified database,

which is often one printable output file.

If your methods aren’t initially validated, if you haven’t been able to

quantify the deviations between your methodology and your sciences and if you

cannot trace backward from the “effect” to the “cause” then

you’ll probably not recognize the diagnostic vectors, nor be able to identify

the sources of problems and formulate solutions.

In the age of eye-candy simulations these practical steps often get lost.

Visuals are good but it’s the numbers, including how they’re derived and how

they’re used, that counts. That’s analysis.

When the numbers are important AEH will be there to

help you.

Oh my! School has started! Good Luck to all the

children.

Al H.

8-24-15